Great libraries and services

Picture perfect.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then the Library of Congress’s

Print and Photograph Division is worth 14 x 109 of them.

There are certain inventions that explode on the scene. The telephone, the automobile, the airplane and the Internet all took off from critical breakthrough into commercially viable products in just a few short years.

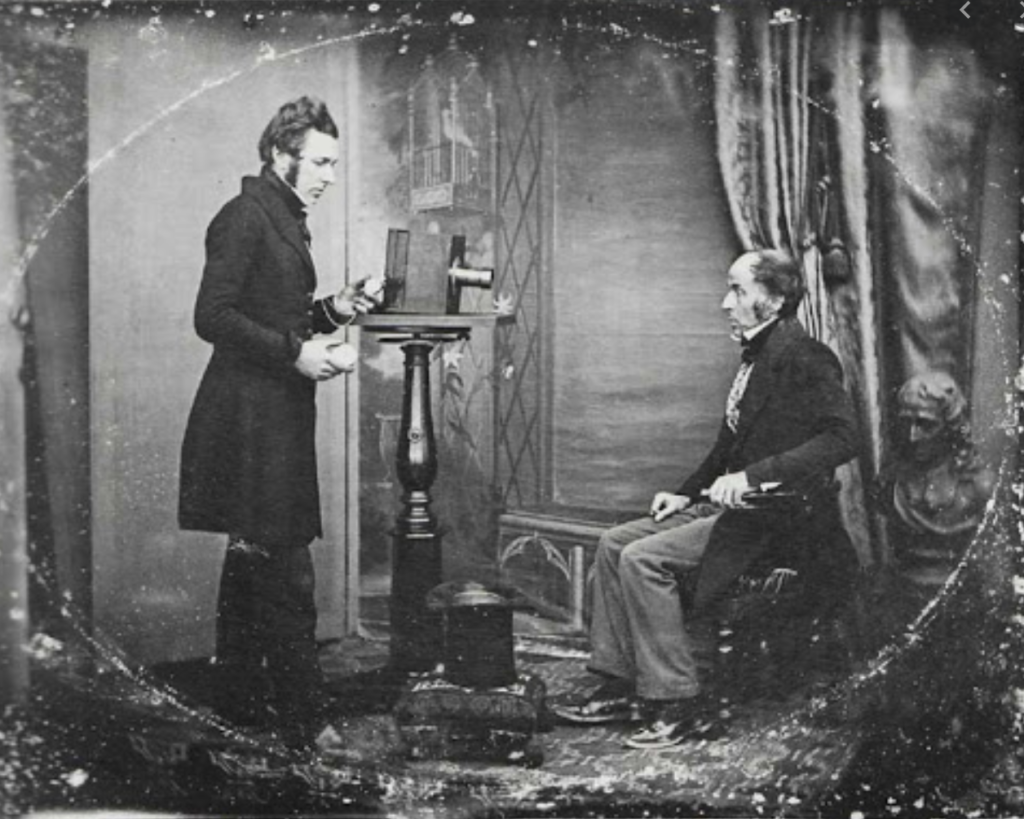

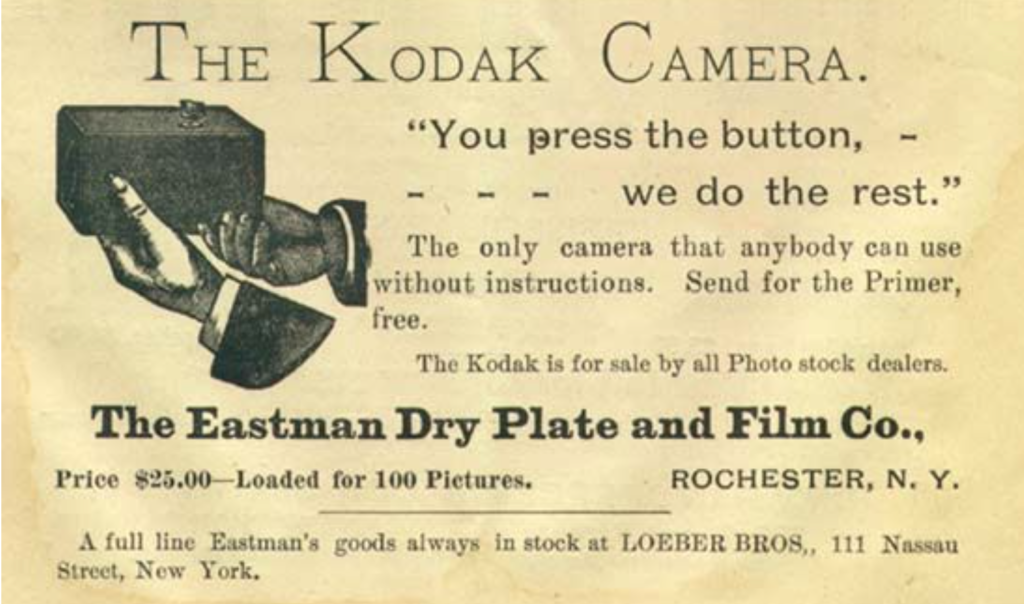

Add photography to that list of overnight sensations. The ability to “fix a shadow” as the early pioneers of photography called their goal, first became practical in the 1840s. But by the time of the U.S. Civil War, anyone who was anyone was having his portrait taken at Mathew Brady’s studio in New York or Washington; soon, the technology became so cheap and the demand to have pictures made was so great that ordinary people clamored to have themselves snapped for posterity. (Nothing back then snapped in the way we mean it today. Early cameras and the chemistry needed to produce an image were notoriously slow. cf. Cellphone photography.)

The result was a society that began to photograph and record everything. There are photos galore of the rich, the famous, the criminal and the historical. There are landscapes and cityscapes and dogs and cats and … look … If you can point at a camera at it or make a print of it, there’s probably a picture of it.

Nowhere can you take a deeper dive into the fascinating and rich pictorial record of the United States than at the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress. It’s an immense collection. Better yet, about 1,000,000 of its 14 million images are digitized and many of its prints are available for low-cost purchase in digital format for printing at home. This is a treasure vault of images for historians, artists, designers and the merely curious. Covering more than 18o years of materials, this is single largest archives of photos and prints in the world. Don’t miss it.

Why so glum? In case you’re wondering why it was everyone looked so somber in those old pictures, it’s not because they couldn’t simple take selfies and post them up to some 1863 version of Instagram. Nor is it because post-mortem photography was a thing in the Victorian era.

Smiling in photos actually has a complicated history. Common wisdom was that the serious expressions were a by-product of the lengthy exposures required to get an image back then (30 seconds to 2 or 3 minutes, depending on the light). Holding a smile that long is near impossible. Try to find a non-blurry child or horse in old photos. They can’t ever stand still long enough.

Makes sense, but that’s only part of the story. Smiling in a painted portrait usually didn’t come across as “happy” back then. Instead, smiles and grins in pictures came across as drunk, crazy or evil. There is still has no single satisfactory answer of why we still say “cheese” and smile for pictures, but it’s probably easier to figure out how the smile became standard than understand the whys and wherefores of duck face.

BONUS ARCHIVE: The Duchenne Medical Photography Archives and Museum

Sometime around 1875, French doctor G.-B. Duchenne used electrical stimulus on the facial muscles to simulate different emotional states and photographed the results. This subject is smiling, but he doesn’t appear particularly happy, know what I’m sayin’?

Web site

Catalog

Collection and Subject Area Guides and Finding Aids

https://www.loc.gov/rr/print/coll/collguid.html

Search tips

Giamatti Research Center at the Baseball Hall of Fame

Resources available at sports halls of fame can make research a slam dunk.

If there is one aspect of American life that cries out for archival preservation, it’s the memory of our sports leagues and competitions. Name your favorite sport and there is more than likely (1) a Hall of Fame for the sport, (2) an associated reference library associated with that hall staffed by smart researchers who can field even arcane questions and (3) usually an archive.

The Giamatti Research Center at the Baseball Hall of Fame, named the former MLB commissioner Bart Giamatti, is one of the great ones. Their research library and archives have old box scores, multimedia records of broadcasts, line-ups, bios of players and just about anything else to make the heart of a diehard [Insert your team here] fan go thumpetty-thump.

The researchers are awesome. Got an unanswerable question about a 1936 Yankees game? Forget about going to the videotape. Go to these researchers. They’ve got all the play-by-play you will ever need.

- Giamatti Research Center

- Library Catalog (Select “Manuscript Archives Collections” to narrow your search for archival holdings under Collection Search.

OTHER SPORTS HALLs OF FAME

Basketball

Web site

The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame

Alas, no searchable archive or research library, though the contacts do list an archivist. The University of Kansas maintains a centralized archive of materials concerning basketball’s inventor James Naismith. Good luck finding a collection of original Air Jordans.

Bowling

Bowling has a hall of fame. I have been to it. I am proud of it.

Web sites

Bowling Museum and Hall of Fame

International Bowling Museum and Hall of Fame

There is no library or searchable archive that I could find, but the international museum does have a feature titled “Explore the Vault” – you might want to tune in to the oxymoronic “Bowling Fashion” for tips on how to stay stylin’ on the lanes.

Football

Web site

Pro Football Hall of Fame

Research

Pro Football Research and Preservation Center

You have to submit requests in writing. Information about how to proceed is on the site.

Golf

Web site

USGA Golf Museum

Research

USGA Gold Museum Research and Resources

Soccer (“Football” to non-Americans)

Web Site

FIFA World Football Museum

Library

The Library at FIFA World Football Museum

Tennis

Web site

International Tennis Hall of Fame

Research

Information Research Center