Picture perfect.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then the Library of Congress’s

Print and Photograph Division is worth 14 x 109 of them.

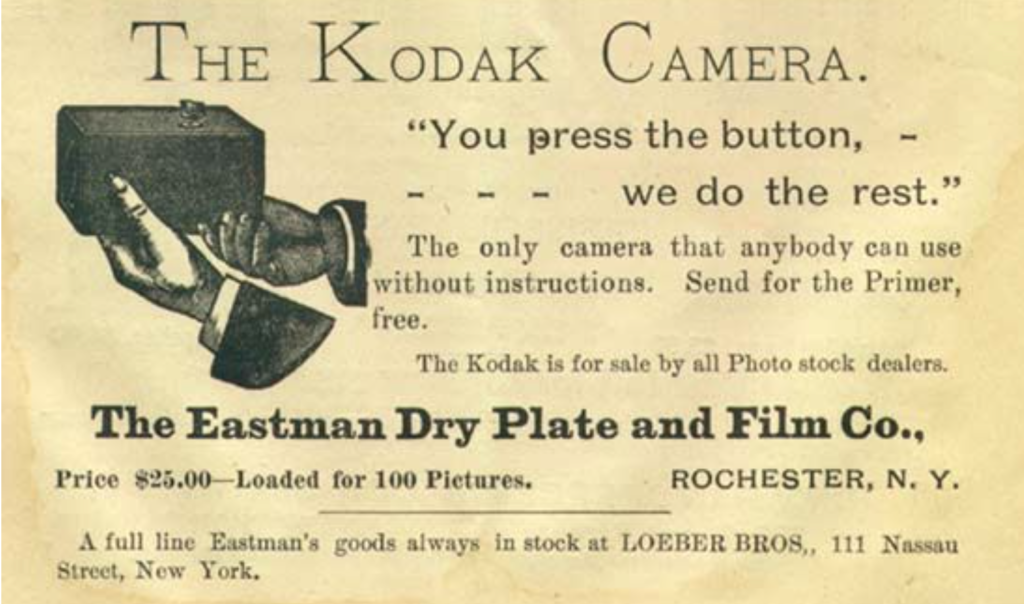

There are certain inventions that explode on the scene. The telephone, the automobile, the airplane and the Internet all took off from critical breakthrough into commercially viable products in just a few short years.

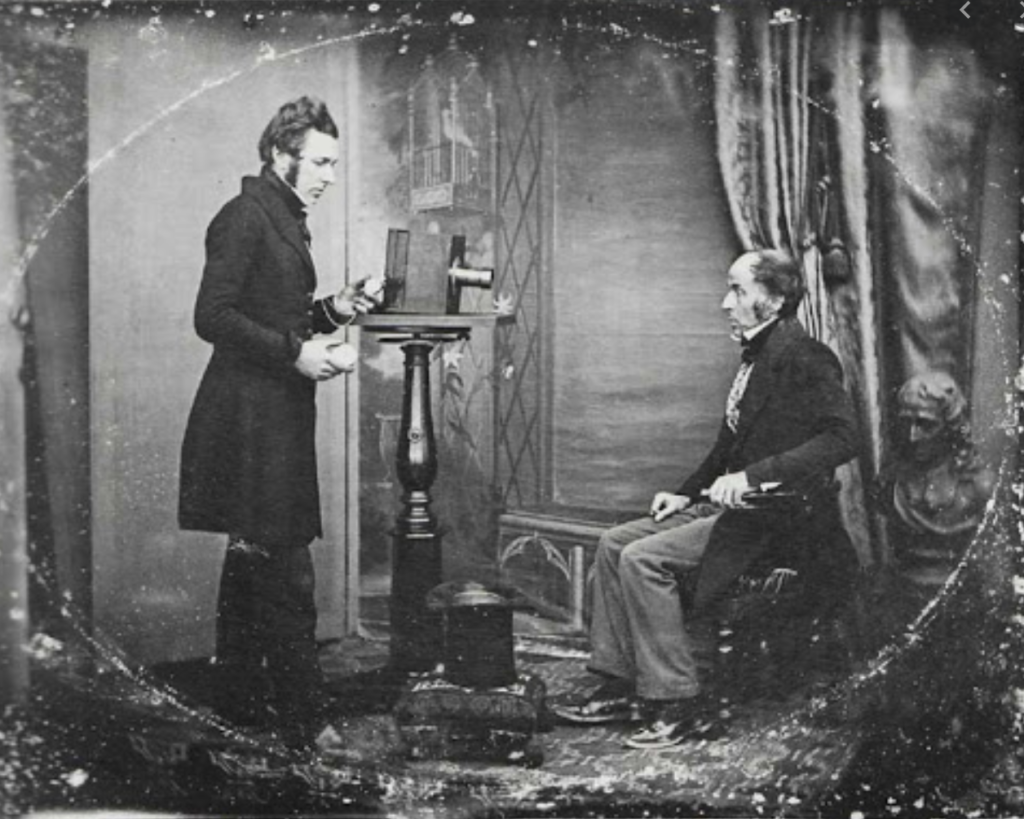

Add photography to that list of overnight sensations. The ability to “fix a shadow” as the early pioneers of photography called their goal, first became practical in the 1840s. But by the time of the U.S. Civil War, anyone who was anyone was having his portrait taken at Mathew Brady’s studio in New York or Washington; soon, the technology became so cheap and the demand to have pictures made was so great that ordinary people clamored to have themselves snapped for posterity. (Nothing back then snapped in the way we mean it today. Early cameras and the chemistry needed to produce an image were notoriously slow. cf. Cellphone photography.)

The result was a society that began to photograph and record everything. There are photos galore of the rich, the famous, the criminal and the historical. There are landscapes and cityscapes and dogs and cats and … look … If you can point at a camera at it or make a print of it, there’s probably a picture of it.

Nowhere can you take a deeper dive into the fascinating and rich pictorial record of the United States than at the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress. It’s an immense collection. Better yet, about 1,000,000 of its 14 million images are digitized and many of its prints are available for low-cost purchase in digital format for printing at home. This is a treasure vault of images for historians, artists, designers and the merely curious. Covering more than 18o years of materials, this is single largest archives of photos and prints in the world. Don’t miss it.

Why so glum? In case you’re wondering why it was everyone looked so somber in those old pictures, it’s not because they couldn’t simple take selfies and post them up to some 1863 version of Instagram. Nor is it because post-mortem photography was a thing in the Victorian era.

Smiling in photos actually has a complicated history. Common wisdom was that the serious expressions were a by-product of the lengthy exposures required to get an image back then (30 seconds to 2 or 3 minutes, depending on the light). Holding a smile that long is near impossible. Try to find a non-blurry child or horse in old photos. They can’t ever stand still long enough.

Makes sense, but that’s only part of the story. Smiling in a painted portrait usually didn’t come across as “happy” back then. Instead, smiles and grins in pictures came across as drunk, crazy or evil. There is still has no single satisfactory answer of why we still say “cheese” and smile for pictures, but it’s probably easier to figure out how the smile became standard than understand the whys and wherefores of duck face.

BONUS ARCHIVE: The Duchenne Medical Photography Archives and Museum

Sometime around 1875, French doctor G.-B. Duchenne used electrical stimulus on the facial muscles to simulate different emotional states and photographed the results. This subject is smiling, but he doesn’t appear particularly happy, know what I’m sayin’?

Web site

Catalog

Collection and Subject Area Guides and Finding Aids

https://www.loc.gov/rr/print/coll/collguid.html

Search tips

Leave a Reply